indoor rearing of cecropia

HYALOPHORA CECROPIA: INDOOR REARING DISPLAYS AND GENERAL NOTES

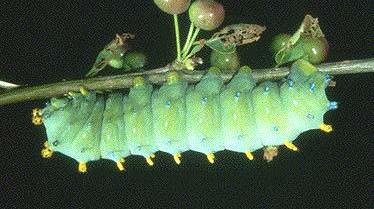

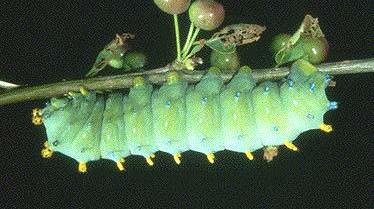

Hyalophora cecropia larvae in their final

instar are spectacular for

both their tremendous size (approx. 11cm / 4.5in.) and beautiful

coloration. Many people come across these monsters feeding on

fruit trees in late summer.

Cocoons and ova are available for purchase. Click on

cocoons for a price list. |

Photo

courtesy of University of kentucky |

Although the rearing of this species on open, indoor displays is labour

intensive, the majesty of these caterpillars makes the effort worthwhile.

Anyone interested in close observation of larvae, in protecting larvae

from

parasitization, or in introducing others to the fascinating world of

insects

should consider the option of indoor rearing.

The breeder, beginner or advanced, can begin with any of the four

metamorphic stages: 1) adult moths, 2) ova, 3) larvae, 4) cocoons.

In this article 1) sources for each metamorphic stage are explained,

2) an indoor rearing technique is described,

3) a general facts list is provided,

and 4) some suggestions are offered.

SOURCES

ADULT MOTHS:

Photo courtesy of Mike Soroka

Gravid females, distinguished from males by their much narrower

antennae and heavier bodies, are attracted to and easily captured at lights

in the early hours of darkness. Ultraviolet (black light) or mercury vapour

lamps radiating outward and upward in the vicinity of host food plants work

especially well from May-July, the flight time for this species. Biological

supply houses, individual dealers, or Home Lighting Centres are good sources

for these light fixtures. An old white bed sheet, secured vertically or

horizontally below the light, aids in the reflection of rays and also affords

the moths a resting place. A visiting moth can be hand picked or netted for

capture.

Virgin females, obtained from one's own reared or

purchased stock

or from cocoons found in the wild, mate readily in captivity. Some breeders

like to "tie out" or tether the females. One makes a half hitch loop near the

end of a soft cotton string, one to two feet (25-50cm) long, and slides this

loop over the female's abdomen up to the juncture with the thorax. The knot

is gently tightened and secured with a second half hitch. Working with a

partner facilitates this process. An assistant can hold the closed-winged

moth with its legs up and grasping a pencil while one slides the loop up to

its proper resting place. Once the female has been secured, she can be tied

out after dark by fastening the other end of the string to a small branch of a

tree. Males often do not arrive until after 4:00 am so "waiting up" is

impractical. One must, however, check the female before daybreak or the birds

will be chirping, "Thankyou, thankyou very much!" The couple should not be

separated, just protected from predation. Snipping the branch and bringing

the pair indoors is recommended. The moths will disengage before nightfall.

Cage matings require less work. The female is placed in a cage

with a mesh small enough to prevent her escape but large enough to allow

mating with a wild male. Square openings of at least 1/2 inch or 1.25 cm work

well. The cage, which need not be much over one cubic foot, should be checked

before day break. I fashion 14 inch high cylindrical cages out of 1/2 inch hardware

cloth and use a dinner plate for a lid over the 8.5 inch diameter top.

| This beautifully marked pair are

copulating inside a screen cage. The pair usually remain coupled for up to twenty

hours and separate naturally in the evening. The female will begin laying eggs

almost immediately so it is wise to keep an eye on her and move her to a bag as soon as pairing is over. |

Photo courtesy of Mike Soroka

|

OVA:

To obtain eggs, place the gravid female in an inflated brown

paper grocery bag. Fold down or twist close the top. Moving the female to a

new bag every day or two and keeping egg batches separate ensure the larvae

from each egg batch will emerge within a short hatching period. The used bag

is then cut into small patches around the ova and these slips are placed side

by side, egg side up, in a dry sandwich tray or small, wide-mouthed container.

Thirty to one-hundred eggs can be handled in a single tray. No food is placed

in the covered receptacle until the small black larvae are seen ten to twelve

days later. They usually eat a portion or all of their eggshells and sometimes

wander for a few hours before congregating on the food supplied after

emergence.

Ova can also be obtained from dealers. Postal shipment should

not be a problem as the eggs incubate for ten to twelve days at room

temperature. If the eggs arrive in a protective sleeve, i.e., aquarium

tubing, turkey quill, etc., they should be gently removed from the protection

and allowed to rest on the dry bottom of the hatching container.

Trying to find cecropia ova in the wild would be much like

looking for a needle in a haystack, but I have found them in groups of 4-5 on

the underside of elderberry leaves in areas of high cecropia populations

(Secaucus, New Jersey, 1960).

LARVAE:

Larvae generally are not shipped in the mail, but they can be

"picked up" from a breeder if you are close. It is not too difficult to find

wild caterpillars in areas of abundance. Since the larvae are voracious

eaters, missing foliage and droppings on the ground invite plant inspection by

collectors and predators. Unfortunately this species is highly susceptible

to parasitic wasps, especially in the fourth and fifth instars and high

percentages of "found" larvae are hopelessly parasitized. In such cases the

larvae grow and spin cocoons, but wasps are all that emerge the following

spring. Look on the underside of host plant leaves to find smaller, parasite

free larvae.

COCOONS:

Cecropia cocoons are huge compared to those of lunas, ios,

polyphemus, prometheas, etc. and they are usually affixed length wise to and

near the base of host shrubs or neighboring plants. These can be found before

or after leaf drop. Those that are spun up higher on the tree are quite

noticeable after leaf drop. Rats and mice also find them and feed on the

pupae. The cocoons are rugged and can be removed from stems by carefully

pulling from the top down. When the cocoons are attached to narrow/upper

stems, clipping is appropriate. The pupa is protected in a denser, inner

cocoon, considerably smaller than its looser, baggy, outer wrapping. A gentle

hefting and shaking can be used to determine the health of the pupa. A very

light rattling or no sound or movement at all indicates parasitization or

disease. A healthy pupa has a noticeable weight and will offer a dull thud

upon shaking.

Many dealers in North America offer cocoons

in the fall, winter,

or early spring. Cocoons may be winter-stored out doors in cages that would

protect them from predation by rats, racoons, skunks, etc., or they may be

kept in refrigerator crispers until the spring. Three to four weeks at room

temperature coupled with at least twelve hours of daylight/daily will often

trigger emergence.

The emergent moth exits the top of the cocoon and must find a

place to "hang" so fluid can be pumped into wing veins for expansion. An

emergence box with screening or cloth sides for climbing should be provided.

INDOOR DISPLAY REARING TECHNIQUE

In the fall of 1996 I had great

success with cecropia larvae which

proved to be quite sedentary and content

to remain near the tips of pin cherry

(Prunus pensylvanica) stems set up in

open, indoor displays. The displays

were used for educational purposes

in P.E.I. schools.

Five or six stems were inserted

through 1.5 centimeter diameter holes

in 2" x 8" spruce scraps which I

picked up for the asking at a nearby

construction site. The spruce was cut

into octagonal shapes and set to float

on seven centimeters of water in 11.4

litre ice cream buckets. The leafy

stems projected at least 30 cm above

the container tops.

A gravid female from a cage mating had been placed in a brown grocery bag

and fifty eggs laid on July 21-22 were moved, still affixed to paper, to a

three litre, wide mouthed, plastic candy jar. Larvae began emerging on the

morning of August 1. Two four-inch-long pin cherry stems with three to four

leaves attached to each were placed in the covered jar after the larvae

emerged. The caterpillars had all moved to the leaves and begun feeding by

evening. No coaxing was necessary.

To help keep the leaves fresh, I wrapped the cut end of each stem in moist

tissue and prevented a moisture build up in the candy jar by enclosing the

tissue wrap in a plastic sandwich bag, collapsed and secured with a twist tie.

I was also concerned with toxins possibly coming from the cut stems which were

allowed to lie flat on the bottom of the container. Pin cherry bark contains

some poisons. My concern, however, may have been unwarranted.

After three days of larvae growth, I removed the stems with caterpillars

attached to the indoor display previously described. The sanwich bag and

moist tissue were removed and the old stems were laid on top of and

perpendicular to the new food. The larvae soon moved to the fresh foliage.

Please note: My open displays were in a small 8' x 8' room where window and

door were kept shut. The evaporating moisture from the open buckets maintained a

humidity essential for caterpillar health. Indoor air is normally too dry for

such a display when caterpillars are small and would easily desicate. For the early stages,

it is best to use a closed container unless you can maintain a proper humidity.

As the larvae grew, their numbers were divided into smaller groupings

for each display. Food changes were accomplished by lifting all stems from

the spruce support, laying the old stems on a newspaper covered, flat surface,

raising and rinsing the spruce, dumping the old water, rinsing the container,

adding fresh water, replacing the spruce, inserting fresh stems and finally

transferring the old stems with caterpillars to the new displays.

The old stems were carefully laid across the tops of or inserted

vertically among the new stems. Care was taken to avoid transfers during

molting, but occasionally one or two caterpillars would be slightly ahead of

or behind their peers. Quiescent caterpillars were moved as carefully as

possible and none were lost due to molting or any other problems. Old stems

were lifted and discarded once the larvae had moved.

Food stayed fresh for six-seven days and was replaced as leaves were

depleted. Larvae spent approximately one week in each instar except for

the fifth instar which lasted slightly more than two weeks. Food had to be

replaced more regularly as the larvae grew. During the final instar, food

was being replaced every two to three days to stay ahead of 5-6 larvae on

each display. Indoor temperatures stayed fairly constant, between 68 and 75

degrees F.

Fresh food was always selected from lush plants. The cut stem ends went

immediately into water to avoid any wilting. To cut down on repeated food

hunts, I gathered more than needed and kept the food fresh by placing it

outside in a shady location with cut ends immersed in a few inches of water.

No special provisions were made for the spinning of cocoons. Some of the

larvae spun at the base of the stems just above the spruce float, but many

spun up in the leaves above the container rim. I let the larvae have at least

two weeks in the cocoon before moving them into cold storage. Cooling before

pupation occurs may destroy all your efforts.

A big surprise was that no larvae attempted to leave the uncovered

buckets. They rarely descended below the bucket rims except to spin cocoons.

It is reported that the larvae of the domesticated bombyx mori have been so

conditioned by the constant human provision of fresh food that they will

starve themselves rather than crawl any distance for fresh leaves. Perhaps

the cecropia larvae, which never had to move far for food, were also

responding to a bit of conditioning.

Another sampling of larvae from the same ova group (July 21-22) was

raised outdoors in a large, vertical sleeve until September 6. These larvae

still had ample food in their enclosure when I brought them in, but all the

upper most leaves had been eaten and the caterpillars had done quite a bit of

walking down branches and the trunk to access foliage on lower branches.

When these caterpillars were brought indoors and set up on the dispays,

the larvae continued walking, frequently crawling down the stems and up and

over the sides of the containers. I had to cover all these set-ups with

inverted buckets for containment. Side by side on a newspaper-covered plastic

floor mat were open displays of sedentary cecropia and covered buckets of

discontented crawlers.

Several displays of the sedentary group were taken into schools and left

uncovered. Fascinated students gently stroked the larvae with their fingers.

The unobstructed viewing of the tireless spinning was also a special treat.

None of the larvae wandered.

Teachers or breeders who supply schools, may want make use of this

technique. A word of caution, however: Make sure you advise the custodian

as to what is lurking in the attractive greenery on the teacher's desk.

HYALOPHORA CECROPIA: GENERAL FACTS

COMMON NAMES: Cecropia, Robin moth

RANGE: Eastern North America to the Rockies, Canada to the deep south

SIZE: This is North America's largest saturniidae with a 5-6 inch

(13-15 cm) wingspan. Caterpillars achieve lengths exceeding

4 inches (10 cm)

LARVAE:

FIRST INSTAR: black with black dorsal and lateral tubercles

SECOND : yellow-green with black tubercles

THIRD : green with four red thoracic tubercles,

yellow dorsal and blue lateral tubercles

FOURTH : identical to third

FIFTH : green with four red-orange thoracic tubercles, yellow

dorsal and blue lateral tubercles, a gray oval

surounding each spiracle

COCOON: Cocoons are of two types:

1) a large, loose, baggy structure,

with a rounded bottom and a tapered neck;

2) a smaller, denser

oblong structure with a tapered neck and bottom. In either

case there is an oblong, inner cocoon of relatively tight

construction. Cocoons are always affixed longitudinally to

a stem and are generally red-brown or brown, although some are

gray or even a drab green. Compared to cocoons of other North

American species, these are monsters, up to 4 inches (10 cm)

long and 2 inches (5-6cm) wide.

FLIGHT TIMES: May to July, primarily in June. In southern states cecropia

have flights recorded from late April to early August.

LIFE SPAN: One year. This species is single brooded and spends the vast

majority of the year in the cocoon/pupa stage.

Adult life: six to eight days

Egg Incubation: ten to fourteen days

Larval Development: five to eight weeks

FOOD PLANTS: Cecropia accept a wide range of food plants, many of which

transport and hold water very well: pin cherry, choke cherry

and other Prunus species; Manitoba maple or box elder; willow;

apple; lilac, pecan in the south, elderberry, American elm,

green ash, southern bayberry or wax myrtle, red maple, poplar,

Amelanchier, Crataegus, and Viburnum species.

TREE DAMAGE: Generally not regarded as a pest, but in high population

densities will defoliate smaller shrubs, i.e., Manitoba maples

in the prairie provinces. Females generally lay a single row

of four to five eggs on the underside of a leaf.

REARING: Fresh or cut food is accepted. Avoid overcrowding and protect

from parasitization. A clean sleeve or cage will minimize risk

of disease. Warmth seems to stimulate growth, but avoid

overheating.

DEMAND: Popular in Europe and North America. Research regarding

distribution diversity, food plant influence on coloration,

pheromone analysis, intergrades with other species of

Hyalophora, etc., tends to go on at various universities and in

private studies. More zoos are setting up live insect displays.

Life histories and art displays create demands. Schools seek

life histories and live displays for educational purposes.

Excellent in salads. I hope not!